China: the search for results

Online marketing is a booming business in China. World Trademark Review looks at how best to protect and promote your brand in the cut-and-thrust world of pay-per-click advertising

Not so long ago, CCTV – China’s flagship state-run television network – was the most important advertising channel in the country, with its annual ‘golden resources’ auction breaking new records year after year. But when the network decided not to disclose the results of its auction for 2014 ad space, analysts saw this as an acknowledgement that it had finally surrendered its top position to Baidu, China’s largest search engine.

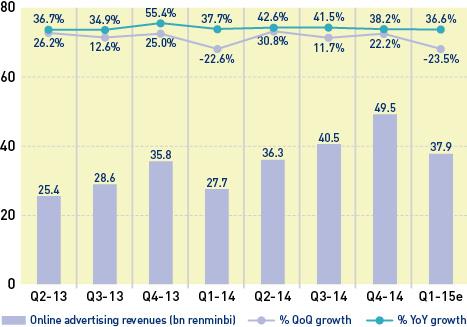

The inevitable shift online has proved phenomenally lucrative for a handful of companies; according to research firm iResearch Global, the internet advertising market in China generated nearly Rmb38 billion ($6.1 billion) in the first quarter of 2015 (usually the weakest quarter for online marketing spend), posting impressive annual growth numbers along the way. Dividing up this large and growing pie, two types of ad and two major platforms stand out. Search engine and e-commerce ads account for around 60% of all revenue in the space, while two platforms are head and shoulders above their peers in estimated ad income: Baidu and Taobao, the consumer-to-consumer (C2C) trading platform run by Alibaba Group.

For foreign brands, the online advertising space presents both valuable opportunities and complex challenges. Much depends on just how strong their foothold in China is. For a relatively new entrant with low brand awareness, getting the company’s name in front of Chinese web users is essential to any growth strategy. On the other side of the coin is the fact that once you have achieved a certain level of recognition, there is likely to be some competition for ad property on search result pages for your trademarked terms. The ads displayed on those pages will affect not only the image and awareness of your brand, but also whether potential customers are ultimately steered towards your preferred commercial channels.

Trademark counsel are likely familiar with the legal issues surrounding branded keywords, especially when it comes to Google’s AdWords service, which has been the subject of protracted litigation. In an article summing up the dismissal of one of the latest cases against Google and Yahoo! for selling branded keywords to third parties, Santa Clara University School of Law Professor Eric Goldman suggested that while a decade of cases has failed to deliver a clear and definitive precedent on the legality of the practice, such suits are likely to die out due to the practical difficulties of prevailing against search engines. The Chinese courts have also heard a number of high-profile cases in this area, which have helped to shape the policies of the major search providers, as well as the options available to brand owners for policing the use of their trademarks on those platforms.

That said, keyword litigation has not disappeared completely: in July, the company that owns the European trademark for IWATCH filed suit over ads for the new Apple Watch triggered by this keyword on Google. Interestingly, however, it seems that the focus may be shifting to the e-commerce space. A US court of appeals recently reversed a summary judgment that exposed Amazon to a lawsuit from watchmaker Multi Time Machine over search results featuring ads for competing brands. More relevant to the situation in China is the fact that branded keywords feature in a recent suit filed by luxury conglomerate Kering SA against Alibaba Group. This suggests that brands might try to use keyword claims as a part of efforts to hold trading platforms accountable for counterfeit goods sold on their sites.

Regardless of the litigation environment, brands have many reasons to monitor the use of their marks in pay-per-click ads. And even beyond the advertising sphere, there are important steps they can take to ensure that a search for their trademarks on China’s leading search platforms projects a positive, accurate brand image and directs consumers to legitimate commercial channels.

Do you, uh, Baidu?

“Even though people are looking more closely at what’s going on in the US, Chinese jurisprudence has been developing along its own trajectory,” says Scott Palmer, a Beijing-based partner with Sheppard Mullin. Court judgments in China’s civil law system do not establish binding precedent, but local counsel generally agree that rulings in a few high-profile cases have established that search engines have a duty of care to examine the legality of advertisements purchased on their platforms.

As in the United States, various companies have tried to sue search engines –in many cases Baidu – alleging indirect trademark infringement. The results have been mixed. Claims are generally brought on Article 36 of the Torts Law, which provides: “Where a network service provider knows that a network user is infringing a civil right or interest of another person through its network services, and fails to take necessary measures, it shall be jointly and severally liable for any additional harm with the network user.”

One of the best-known disputes pitted automaker Volkswagen against Baidu. At issue were ads that displayed on the results page for a search of Da Zhong, the Chinese characters for ‘Volkswagen’. The Shanghai Intermediate Court ruled that sponsored links differ from organic search results in that Baidu is in a position, and under an obligation, to review their legality. In the case of a mark with a certain degree of fame, such as Da Zhong, the site should have taken steps to determine whether the ad buyer had any connection with Volkswagen.

In a handful of other cases Baidu was held not liable for infringement, in part because it had discontinued services to the ad buyer after becoming aware of the infringement. According to George Chan of Simmons & Simmons, the step of establishing knowledge is central to such cases. If a mark has a certain level of market recognition, the search engine may be found to have constructive knowledge of infringement. “If a trademark is not well known, it will be difficult for its owner to argue that the search engine should have known that an ad displaying the trademark without authorisation is unlawful, until the owner contacts the platform directly, usually through a formal complaint,” Chan notes.

The prevailing trend in these decisions “may be interpreted as service providers being subject to a duty of care,” continues Chan, “and it would be negligent on their part to not offer an aggrieved party the means to file a complaint in relation to their trademark right”. As a result, the major search platforms have become increasingly responsive to brand owners’ concerns. “At least in terms of the larger providers, they are much more vigilant and careful about these things,” says Palmer. “Generally speaking, they will investigate if you lodge a complaint; and indeed, if it looks as though they may not have discharged their duty of care, the chances are these sites will respond.”

The upshot is that, as in the United States, claims against search engines will likely remain rare. But with those platforms more willing than ever to investigate trademark abuse on the part of third parties, companies should still be monitoring the space closely for misuse of their brands.

Figure 1: China online advertising revenues Q2 2013-Q1 2015

Source: iResearch Global

Figure 2: Market share of different advertising forms in China, Q2 2013-Q1 2015

Source: iResearch Global

Figure 3: Top 10 online advertising publishers by estimated ads revenue in Q1 2015

Source: iResearch Global

The importance of monitoring

Meanwhile, companies remain keenly interested in tracking how their brands are used online. According to Daniel Cai, general manager of search engine marketing agency The Egg, “Our clients are leaders in their industries, and even though some of them don’t have an online marketing team in China, they want to know what people are saying about their brand and whether it is being taken advantage of by competitors.” Cai explains that the process for complaining about the use of a trademark in a competitor’s ad text is relatively straightforward – provided that the company has already obtained IP protection in China: “To ask search platforms like Baidu and Haosou [a search brand of Qihoo 360] to screen ads for your brand, you have to have a Chinese registered trademark; a foreign right does not help at all.”

A Baidu representative outlined the platform’s policies to World Trademark Review. As is standard with Google and other global search engines, Baidu has no specific restrictions on using a third-party trademark as a keyword; but where a mark is used in the text of an ad, brands have some scope to complain. “Theoretically speaking, Baidu does not allow clients to use a third-party trademark in their text,” said the representative, “But there are a few exceptions – for example, when the clients have obtained authorisation from the trademark owner to use it, or when a client is simply describing the original meaning of a certain trademark and is not using it as a business sign for commercial purposes.”

Baidu’s complaints platform can be found at tousu.baidu.com, which has a section devoted to trademark issues. If a company is concerned about use of its marks in ads, it is important to take proactive steps. As the Baidu representative pointed out: “Given that there are over 10 million registered trademarks on the Chinese mainland alone, Baidu will not be able to constrain every action that goes against this policy immediately.” Once the Baidu team receives a complaint, it will verify the trademark registration and review the ad in question against Baidu’s policies and the laws. “If it is serious or has received multiple complaints,” said the representative, “Baidu could shut down this client and never allow it to publish any ads through Baidu.”

A wide range of entities might be using your trademark improperly in online ads in China, beyond just direct competitors. “A lot of third parties out there sell keyword advertising,” says Palmer. “They are basically ad companies and one of their services is to help you get a higher profile in the market, and one way that they’ll do this is by selling you certain keywords.” These activities would typically fall under China’s Advertising Law or Anti-unfair Competition Law, he continues, adding that proving intent and infringement may come down to looking at what their promotions look like. “If there’s a fairly egregious promotion or one that says something like, ‘Get an edge on your competitors’, then a court might be sympathetic to your claim. There aren’t too many of these kinds of cases published, so it is hard to tell what kind of track record there is with such claims.”

Brand Verity is a service that helps brand owners to monitor the use of their trademarks in Chinese search engine ads, including on Baidu and Sogou. According to marketing manager Sam Engel, clients use its service on Chinese platforms mainly to enforce existing agreements with other companies: “In China, we are largely monitoring for direct relationships that the brand can enforce – typically with marketing partners or affiliates who brands do not want bidding on their branded keywords.” Engel says that these agreements are often large-scale international partnerships. A marketing partner or affiliate might feel that it can get away with bidding on branded keywords in China because brands are less likely to monitor there. Keeping an eye on the Chinese search space can put an end to this practice and ensure that these types of agreement are honoured.

Keeping tabs on local affiliates in China – whether they are joint venture partners, authorised resellers or licensees – is critical for any foreign business and monitoring search ad activity is one tool to help do this. Licence agreements increasingly include provisions on how the brand owner’s trademarks can be used online by the licensee. “In some ways, it’s a balancing act between controlling your IP and providing licensees with the tools for success,” says Chan. Major players such as renowned luxury brands can afford to control their entire supply chains in China, but for small and medium-sized companies, this may not be practical. “If you’re a smaller company, you want assistance with the development of your brand in China and consequently you don’t want to restrict your licensee’s ability to promote your brand if you’re just trying to gain a foothold,” Chan explains. Cutting a deal to allow a local partner to advertise using your brand online in China may be the best option in such cases, but brands should carefully monitor these activities for compliance.

Aside from any legal concerns, tracking the ads being bought on a company’s keywords can provide valuable commercial intelligence. For companies with a general visibility problem in China, watching the ads that show up in branded searches can help them to assess the competitive environment and perhaps understand why the brand has not made as much of an impression on Chinese consumers as they might have hoped. The competition in this market, for keywords as well as customers, may be quite different from that in other countries and require a different strategy.

The Nike BrandZone pictured here takes up much of the first search results page on Baidu, and includes interactive content as well as multiple links and images. No competing paid advertisements are visible ‘above the fold’.

Source: Baidu search conducted August 1 2015

E-commerce comes to the fore

E-commerce has been in the spotlight of late due to government anti-counterfeiting initiatives, with Alibaba Group in particular finding itself in the hot seat more often than not. The company was on the receiving end of a sharply worded State Administration of Industry and Commerce white paper (which the agency later retracted and described as a meeting summary) early this year, and in May was sued by luxury conglomerate Kering over the availability of counterfeits on its platforms. Selling pay-per-click ads is certainly an important part of the company’s business; could it play a role in the counterfeiting complaints against the company? “The use of keywords by e-commerce platforms is very relevant right now,” says Chan. “Sites like Alibaba don’t directly sell products, but provide a platform, and as part of that they sell pay-per-click advertising. Just like on search engines, you can request or bid for keywords on sites like Taobao for the purposes of generating more traffic.”

Indeed, Kering raised the issue of branded keyword sales several times in its US district court suit. The brief notes that Alibaba derives significant revenue from the sale of keywords, including those that are trademarks of Kering. The suit claims that pay-per-click ads bought on branded keywords are typically given the most prominent placement on a search results page and are not meaningfully distinguished from organic results. “In this way,” the suit continues, “the Alibaba Defendants directly cause consumer confusion as to the origin, authorization, sponsorship, and affiliation of the merchants who have bought trademarks as keywords and the products that such merchants sell, despite the fact that many, if not most, such products are, in fact, Counterfeit Products.” The suit goes further to allege that when a user searches using the keyword ‘Gucci’, for example, Alibaba’s algorithms will suggest ‘related’ keywords such as ‘cucci’ and ‘guchi’. Maintaining that Alibaba’s algorithms must be sophisticated enough to know that these are confusingly similar terms to ‘Gucci’, the plaintiff contends that these keyword suggestions are intended “either to steer customers to Counterfeit Products or to confuse the customers who may believe they are being presented with genuine Gucci Products”.

Chinese search engines offer several unique ways for brands to shape the images brought up by a simple web search

Alibaba Group senior legal counsel David Ho explained the company’s policies when it comes to branded keywords: “Keyword searches are based on a bidding process in which sellers and brand owners are able to participate. We already have various manual and automated measures in place to help identify any third-party trademark listings on our marketplaces, including pay-for-performance advertisement listings. We also welcome the help of brand owners to help us identify any infringements we may have missed and have created a notice and takedown system for brand owners.” Ho encourages brand owners to set up accounts with notice and takedown services AliProtect and TaoProtect, where they can use an electronic system to upload IP documentation and submit requests. Subjects of a takedown notice have three days to refute the allegations or produce evidence of the goods’ authenticity. While Alibaba has a zero-tolerance policy for individual counterfeit listings, account holders are dealt with through a three-strikes rule.

Whatever the fate of the Kering lawsuit, it will be interesting to see whether it influences other companies to pay closer attention to keywords as a counterfeiting issue in terms of their use on e-commerce sites. China’s most recent Trademark Law includes provisions that are relevant to this question. Article 57, which defines ‘infringement’, includes “the intentional provision of facilitating conditions for acts of infringing another’s exclusive trademark rights”, and the implementing rules make clear that supplying an internet platform for transactions constitutes such “facilitating conditions”. “This could be a shot in the arm that makes it a bit easier to claim direct infringement; but again, you have to show intent, which is extremely difficult if platforms are discharging their duty of care,” warns Palmer. He says the analysis for assessing secondary liability differs from that used in pure search engine cases: “Unlike a search engine, e-commerce sites are providing a platform that is specifically geared towards making goods transactions efficient, fast and lucrative for everybody involved, including themselves. The analysis looks at whether they are aiding and abetting, as well as whether they are benefiting to some extent, so the nature of the business would definitely affect that analysis.”

Again, though, as with search engines, there are several other reasons beyond potential litigation why brand owners should be monitoring such activity. For example, many companies are taking a closer look at how licensees use their marks on online trading platforms. “What is common now is to put a provision in a licence agreement where any kind of e-commerce ad needs to be preapproved and follow certain policies set by the licensor,” says Palmer. “This is critically important, particularly for companies that sell fast-moving consumer goods, because in order for them to get a handle on what’s infringement and what’s not, they need to be able to distinguish authorised from unauthorised sellers on sites such as Taobao”. With preapproved ads, rights holders know right away whether a certain listing is authorised, minimising the chance that genuine licensees will be swept up in a blanket takedown request made to a site such as Taobao.

Search results for Burberry, which does not have a BrandZone. Burberry’s official site (signalled by the blue box next to it) appears at the bottom of the page as an organic result. The official Burberry site appears as the highest-ranked paid search result. The second paid result is translated by Google as “Imitation Burberry – more than a thousand high-quality fine imitation Burberry”. The third paid result reads “Burberry discount counter genuine goods”. Between the paid content and the official Burberry site is the entry for Burberry on Baidu Baike, the site’s Wikipedia-like platform.

Source: Baidu search conducted August 1 2015. Translations by Google Translate

Getting results

First impressions are important, so in addition to watching for trademark infringement in pay-per-click keyword ads, there are some additional steps that companies may wish to take to influence the experience of users when they see the brand’s search results. The most obvious: simply bid for ads on your own keywords. But Chinese search engines offer several unique ways for brands to shape the images brought up by a simple web search.

Probably one of the best known is the option to have a Baidu BrandZone. As the image on page 21 illustrates, BrandZone effectively takes over two-thirds of the first search result page. With users able to click through multiple tabs with different categories of product, it has the effect of a mini-store, and the ability to include images and rich content such as videos gives owners many more options to shape their brand image. Because BrandZones are sold only to verified rights holders, customers have a high degree of confidence that they are dealing with the genuine outlet. And for companies concerned about competing keyword ads, it is the easiest way to push these below the fold and give users the chance to interact with the brand’s official site first – Baidu claims that over half of everyone who views a BrandZone interacts with it in some way. However, this is a very expensive option, according to marketing consultants, and thus mainly an option for blue-chip properties with big budgets. The advantages are clear, though – as Baidu’s own website points out, it is the best way to prevent competitors from capitalising on your brand equity.

The smaller (but quickly growing) alternatives to Baidu offer comparable services. Qihoo 360, whose platform HaoSou is the most formidable of these, has its own analogous option called Brand Express. Assessing whether these opportunities make sense from a branding perspective may pose a new dilemma to brand owners, given the lack of similar set-ups at the major players in the United States and Europe (Google briefly trialled the sale of large photographic banners at the top of certain branded searches, but abandoned the idea). According to Cai, “The ROI can be quite low on a BrandZone, because it’s very expensive and it requires collaboration with other marketing activities like social media to generate the volume of branded searches. If the search volume is quite low, then companies will not get much out of it.”

A more economical option is what Baidu calls Brand Starting Line. “It’s a mini-version of BrandZone, though it doesn’t take over the entire first results page,” explains Cai. This feature allows owners to pay by the city, allowing them to prioritise their most important markets in China. But regardless of which option brands choose, Cai says that direct interaction with consumers is key: “It’s important to do a lot of social media outreach to promote awareness of your brand; you’ll see your search volumes go higher and higher.”

Baidu, along with some of the other search engines, has a few platforms which do not have direct counterparts in the United States, but do provide some low-cost opportunities to push brand-approved content to the top of results pages. Baidu, Sogou and Haosou all have their own Wikipedia-like sites, known as Baike. Brand owners are doubtless aware of Google’s relatively new Knowledge Graph feature, which pulls Wikipedia information and displays it in the upper right-hand corner of the results page, giving some free organic real estate to most brands. In a similar way, entries on Baidu Baike, for example, are ranked highly in results (see image opposite). “There is a paid version with advanced features which allows you to have a customised page and content,” says Cai. “There is a dedicated team of moderators overseeing company-related edits, with strict moderation rules, so it is very difficult for third parties to leverage your brand wiki and change it for their own purposes.” Given their prominence in searches, brands should ensure that their Baike pages are accurate and up to date. Baidu also offers a feature called Wenku, which is a document upload and sharing platform for PDFs, Word documents, Excel files and PowerPoint presentations, similar to services such as Scribd or SlideShare. Cai says that his company helps brands to upload materials such as white papers to help get more official content in front of searchers.

There is real and meaningful competition in China’s web search sector, with emerging platforms posting impressive growth numbers and slowly making incursions into Baidu’s market share. As the major players vie for both eyeballs and advertisers, this contest is sure to spur further change and innovation in the services which are offered to search users and brands alike. Trademark counsel should work with their local lawyers and marketers to ensure that they adapt to the changing realities of Chinese online searches.