Mexico: Make your product pop – but make sure it is well protected

Products need innovative strategies to stand out on shop shelves, especially in the food and beverage sector. While such marketing can increase sales, it also risks compromising trademark protection

The food and beverage sector is without question one of the most competitive and fastest-moving sectors – a space in which creativity, marketing and IP protection must all synchronise. For a product to become a hit on shop shelves requires marketing strategies which use all types of distinctive sign and even so-called ‘fluid use’. While these strategies and innovations are designed to increase sales and product penetration, they also carry the risk of compromising protection from a trademark point of view.

Manufacturers and service providers face constant pressure to innovate because of competition and consumer behaviour, especially in the food and beverage sector. Purchasing decisions are influenced not only by the quality of a particular product, but also by factors such as overall appearance, colour or even texture.

However, making a product attractive while maintaining adequate protection remains a challenge given that different jurisdictions provide different types and levels of protection. A rights holder should first look for local counsel before introducing distinctive signs into the market or changing existing ones.

Distinctive signs in Mexico

The Industrial Property Law establishes that the exclusive right to use a mark derives from its registration and not from its use or priority of adoption. Although certain rights arise as a result of use, it is not a good idea to trade in commerce using an unregistered distinctive sign.

Article 88 of the Industrial Property Law defines a ‘trademark’ as “any visible sign that distinguishes goods or services from others of the same type or class in commerce”. Article 89 provides that the following signs may also constitute a trademark:

- denominations or visible devices which are sufficiently distinctive and capable of identifying the goods or services that they intend to cover from others of the same class or type;

- three-dimensional (3D) shapes;

- commercial names and denominations or corporate names; and

- the name of an individual, provided that it does not lead to confusion with a registered mark or a published commercial name.

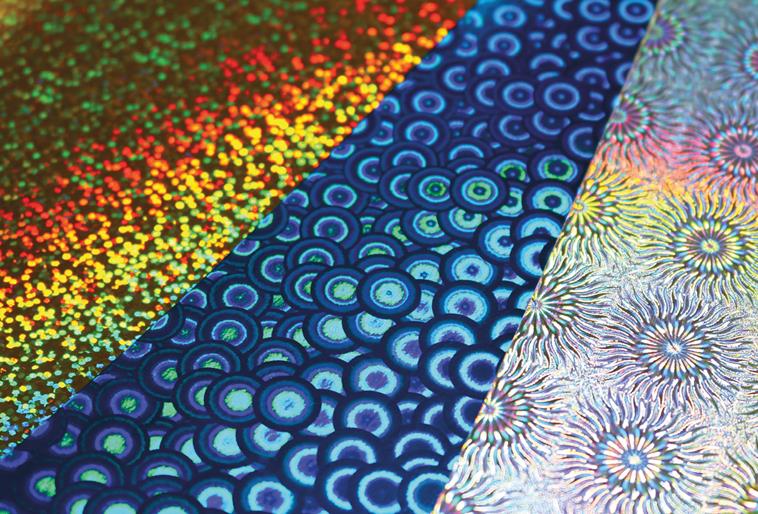

Motion signs such as holograms can function as source indicators but cannot be protected as trademarks in Mexico

Since only visible signs can be considered trademarks, it follows that non-visible signs such as sounds, scents or textures cannot be registered as trademarks, even where these serve as source indicators.

In addition, motion signs such as holograms, which can certainly function as source indicators, cannot be protected as trademarks. Article 90 expressly excludes figures or 3D shapes which are animated or expressed in motion from protection, while Article 90(V) prohibits the registration of individual colours, digits or letters, unless these elements are combined with others or are highly stylised.

Three-dimensional shapes are fully protectable in Mexico as trademarks without the need to prove secondary meaning or acquired distinctiveness. However, in order to qualify for protection as 3D marks, the shape must be distinctive, non-functional and not determined by the product’s nature.

Protection for 3D marks can provide a crucial advantage for food and beverage manufacturers as consumers in this sector are particularly guided by the overall appearance and shape of a product when trying to differentiate one product from another on shop shelves.

What about slogans?

Under the Industrial Property Law, phrases that are intended to advertise goods or services can be registered as commercial slogans. The main difference between a trademark and a commercial slogan is that while trademarks are designed to function as a source indicator and to distinguish goods or services, a slogan is intended merely to advertise the goods or services in question.

Commercial slogans are protected in the same way as trademarks. Consequently, protection for slogans can be renewed and the rights derived from registration can be fully enforceable. In fact, a commercial slogan can be cited as an impediment to the registration of a trademark and vice versa.

Should fluid use be considered?

Under Mexican law, a trademark must be used as registered. Any changes applied by the rights holder must not alter the mark’s distinctive character in order to renew the registration or consider it effective use. In view of this, it is always worth discussing with counsel the implications of using a mark in a fluid way (eg, by incorporating new elements) or discontinuing its use as registered.

The consequences of fluid use range from the risk of facing a non-use cancellation action to the impossibility of asserting rights when filing for infringement and difficulty when it comes to renewing the registration.

Another consequence might be the inadvertent infringement of third-party rights, if the fluid use results in a mark which is confusingly similar to another registered mark.

If a third party files a cancellation action based on the fact that the mark is no longer being used as registered, the rights holder must produce evidence of actual use to prove that the trademark has been used in commerce for at least three years preceding the filing of the non-use cancellation action.

If evidence of the mark being used in a fluid way is produced, the trademark authority must determine whether the new elements modify the mark’s distinctiveness.

In an infringement action initiated by the owner of a fluid mark, the alleged infringer may well counterclaim with a non-use cancellation action, arguing that the mark is no longer in use. Alternatively, if the infringement derives from the adoption of elements which were added to the mark after it was registered, it is unlikely that an infringement proceeding would prevail.

Updating registrations

Trademarks are subject to constant evolution, with designs often modified to meet commercial needs. Given this, it may become necessary to replace an existing registration with one that incorporates a new design, even though this means losing the seniority acquired by the original registration.

One alternative can be to obtain a registration for the word mark alone; this registration will gain seniority – provided that the word part of the trademark remains unchanged – and will eventually become uncontestable, while the rights holder can update the registration for the composite mark without incurring any significant risks.

Final considerations

In an ideal scenario, food and beverage manufacturers would be able to use the same trademark on all of their products around the world. However, in practice, protection is subject to various factors. For instance, Mexico applies a standard of inherent distinctiveness for registration. Consequently, descriptive marks can never be protected even where they have acquired secondary meaning. This is a particular challenge for owners of international food and beverage brands which may have invested millions of dollars in advertising to ensure that consumers from all over the world can identify the source of the goods.

Although scents, sounds and textures can provide brands with a commercial advantage, they cannot be protected as trademarks in Mexico under the Industrial Property Law.

Trademark clearance also plays an important role in Mexico. Since Mexico is a registration country, the main source to consider is the database of the Mexican Institute of Industrial Property (MIIP). However, since Mexico ascended to the Madrid Protocol, the World Intellectual Property Organisation’s database must also be considered as, in some cases, designations for Mexico may take months to appear in the MIIP database.

Local practice should be taken into consideration and local counsel consulted when determining whether a proposed mark has a good chance of being registered under domestic provisions and criteria, and whether it would be more suitable for a seasonal strategy or as a long-term trademark.

Ideally in-house counsel should play the role of an orchestra conductor by advising and serving as a link between the marketing and R&D departments and IP counsel – areas that must play together in harmony in order to optimise resources, obtain the best available protection and result in food and beverage products commanding a successful presence on the shelves.

Gerardo Parra obtained his law degree in 1998 from the Universidad Panamericana. He holds a postgraduate qualification from the same university and graduated with honours from the John Marshall Law School, Chicago, where he obtained an LLM in IP law. Mr Parra works in the trademark department of Uhthoff, Gómez Vega & Uhthoff and is fluent in Spanish, English and Italian.